1. Introduction

Catalytic converters are indispensable components in modern internal combustion engine vehicles, serving as the primary aftertreatment technology for mitigating harmful exhaust emissions. Their critical role lies in transforming toxic pollutants—such as unburnt hydrocarbons (HC), carbon monoxide (CO), and nitrogen oxides (NOx)—into less noxious substances like water vapor, carbon dioxide, and nitrogen gas 10. This report delves into the fundamental scientific mechanisms by which various exhaust gas components and operating conditions degrade the performance and lifespan of catalytic converters. We will explore the intricate chemical and physical processes that lead to deactivation across different converter architectures, providing a comprehensive understanding of these complex interactions.

2. Catalytic Converter Architectures and Operating Principles

Catalytic converters are sophisticated chemical reactors designed to facilitate specific redox reactions. Their core structure typically consists of a ceramic (cordierite) or metallic (fecralloy) honeycomb monolith substrate, which provides a high geometric surface area for the catalytic washcoat 37. This washcoat, a porous layer usually composed of high surface area metal oxides like gamma-alumina (γ-Al2O3), silica (SiO2), titania (TiO2), ceria (CeO2), and zirconia (ZrO2), is crucial for dispersing the active catalytic materials 40. The washcoat thickness typically ranges from 20-40 µm, corresponding to loadings of approximately 100 g/dm33 on 200 cpsi (cells per square inch) substrates and up to 200 g/dm33 on 400 cpsi substrates 57. The choice of substrate and washcoat material significantly influences the catalyst’s thermal stability, mechanical strength, and overall performance 37.

Different types of catalytic converters are employed depending on the engine type and emission targets:

2.1. Two-Way Catalytic Converters

Primarily used on diesel engines, two-way catalytic converters focus on the oxidation of hydrocarbons and carbon monoxide 10. They typically contain platinum (Pt) and/or palladium (Pd) as active noble metals.

2.2. Three-Way Catalytic Converters (TWCs)

TWCs are the standard for gasoline engines and are designed to simultaneously reduce three major pollutants: nitrogen oxides (NOx), carbon monoxide (CO), and unburnt hydrocarbons (HC) 4. This simultaneous conversion is achieved through a delicate balance of oxidation and reduction reactions, requiring the engine to operate within a narrow stoichiometric air-to-fuel (A/F) ratio window (λ = 1), typically between 14.6 to 14.8 for gasoline 5.

The active materials in TWCs are predominantly noble metals:

- Platinum (Pt) and Palladium (Pd) primarily catalyze the oxidation of CO and hydrocarbons 1. The oxidation of hydrocarbons, such as propane (C3H8), propene (C3H6), and methane (CH4), is considered similar to that of CO 1. Activation energies for HC oxidation on Pd/Rh and Pt/Pd/Rh catalysts range from 105-125 kJ/mol, with methane oxidation being particularly challenging 1.

- Rhodium (Rh) is crucial for the reduction of nitrogen oxides 1. Rhodium active sites facilitate the weakening of the N-O bond in NO, leading to the formation of N2 2.

The primary chemical reactions occurring in a TWC are:

- NOx Reduction: 2NO + 2CO → N₂ + 2CO₂ 3

- CO Oxidation: 2CO + O₂ → 2CO₂ 3

- Hydrocarbon Oxidation: 2C₂H₆ + 7O₂ → 4CO₂ + 6H₂O 3

Base metal oxides, particularly cerium oxide (CeO2) often in a CeO2-ZrO2 mixed oxide form, play a vital role as oxygen storage components (OSC) 1. This oxygen storage capacity helps buffer fluctuations in the A/F ratio, extending the “catalyst window” and maintaining high conversion efficiency even during transient engine operation 5. For instance, Monolithos Catalysts & Recycling Ltd. developed PROMETHEUS, a TWC catalyst incorporating Cu, Pd, and Rh nanoparticles supported on a CeO2-ZrO2 mixed oxide with high OSC, demonstrating the importance of these mixed oxides 1.

2.3. Diesel/Lean NOx Catalytic Converters

Diesel engines operate with lean fuel mixtures (excess oxygen), which makes NOx reduction challenging for traditional TWCs. Specialized systems are employed:

- Diesel Oxidation Catalysts (DOCs): These are primarily used to oxidize CO and hydrocarbons, including the soluble organic fraction (SOF) of particulate matter, and to oxidize nitric oxide (NO) to nitrogen dioxide (NO2) 10. The NO2 is then used in downstream components like Diesel Particulate Filters.

- Diesel Particulate Filters (DPFs): DPFs are designed to physically trap particulate matter (soot and ash) from diesel exhaust. They are typically made of porous ceramic materials. Soot deposition on DPFs occurs in stages: deep bed deposition, particle tree growth, particle tree connection, and soot cake layer formation 28. The soot cake layer can reach a thickness of 20-50 microns 28.

- Selective Catalytic Reduction (SCR) Systems: SCR systems reduce NOx emissions by injecting a reductant, typically urea (which decomposes to ammonia, NH3), into the exhaust stream upstream of a catalyst. The ammonia then selectively reacts with NOx over a catalyst, usually a zeolite-based material, to form N2 and H2O. NOx conversion efficiency in SCR systems is influenced by catalyst temperature, gas velocity, and the NH3/NOx ratio 48.

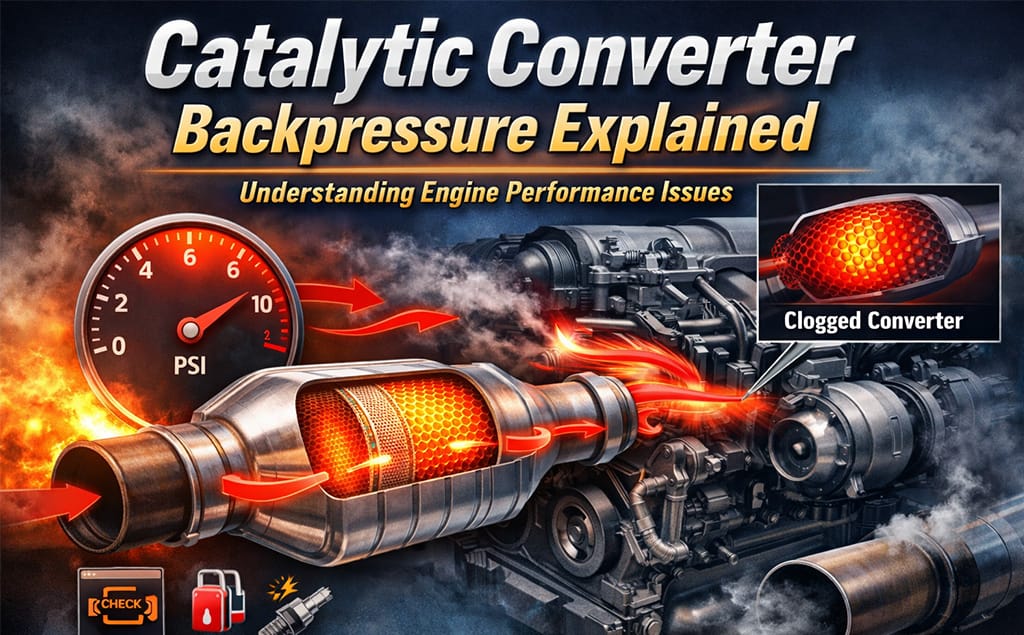

The overall efficiency of catalytic converters is influenced by factors such as cell density, wall thickness, and the geometric surface area of the substrate 38. Higher cell density generally improves performance by increasing mass transfer surface area but also increases pressure drop 38.

3. Exhaust Gas Components: Reactants, Poisons, and Promoters

Exhaust gas is a complex mixture of components, some of which are intended for conversion by the catalytic converter (reactants), while others can severely degrade its performance (poisons) or, in some cases, enhance its activity (promoters).

3.1. Reactants

The primary target pollutants for catalytic conversion are:

- Unburnt Hydrocarbons (HCs): Resulting from incomplete fuel combustion.

- Carbon Monoxide (CO): A product of incomplete combustion.

- Nitrogen Oxides (NOx): Formed at high temperatures during combustion, primarily NO and NO2.

3.2. Poisons

Catalyst poisoning is the deactivation of a catalyst by chemical means, distinct from thermal degradation or physical damage 6. Poisons typically chemically bond to or react with the catalyst’s active sites, reducing their availability and increasing the diffusion distance for reactant molecules 6. This leads to an increase in light-off temperature and a decrease in maximum conversion efficiency 7. Poisoning can be reversible or irreversible, with reversibility often enhanced at higher temperatures in a reducing environment 8.

Key catalyst poisons include:

- Lead (Pb): Historically, leaded gasoline was a major source of lead poisoning. Lead, in forms such as elemental lead, lead(II) oxide, lead(II) chloride, and lead(II) bromide, alloys with the noble metals or coats the catalyst surface, preventing contact with exhaust gases 610. A deposition of merely 0.5% of the catalyst’s weight can lead to a 50% drop in conversion efficiency 7.

- Sulfur (S): Naturally present in petroleum fuels and lubricants, sulfur compounds (SO2, SO3, H2S, and various sulfates) adsorb onto the catalyst surface, particularly affecting palladium (Pd) 7. SO2 can be oxidized to SO3 and stored within the catalyst 7. Sulfur poisoning decreases both light-off and warmed-up activities, significantly increasing the light-off temperature 7. For instance, high sulfur fuel (575 ppm) can drastically increase the light-off temperature compared to low sulfur fuel (40 ppm) 7.

- Phosphorus (P): A common component of lubricating oil additives, particularly zinc dithiophosphate (ZDDP), phosphorus compounds can form phosphates (e.g., cerium, zirconium, aluminum, and titanium phosphates) and zinc pyrophosphate 7. These compounds interact with washcoat components like Al2O3 and CeO2, forming a glaze that seals the catalyst surface and restricts gas passage 7. Phosphorus poisoning is often more pronounced than hydrothermal aging alone and primarily affects the oxide components rather than the noble metals 11.

- Zinc (Zn): Also originating from lubricating oil additives like ZDDP, zinc converts to oxides during combustion and contributes to the formation of a glaze over the catalyst surface, reducing efficiency by covering active sites 7.

- Silicon (Si): Sources include coolant leaks, contaminated fuels (especially improperly recycled methanol or ethanol in biofuels), and silicone sealants 7. Silica (SiO2) can clog the protective sheath of oxygen sensors, restricting gas diffusion and leading to incorrect air/fuel mixture control, which in turn causes rough engine idle, poor fuel economy, increased emissions, and catalytic converter damage 7. It can also deposit directly on the catalyst surface.

- Ash: Non-combustible residues from fuel and lubricating oil combustion, ash can accumulate on the catalyst surface, physically blocking active sites and contributing to masking and pressure drop 40.

3.3. Promoters

Certain components or additives can enhance catalyst activity or durability:

- Ceria (CeO2) and Ceria-Zirconia (CeO2-ZrO2): These mixed oxides are widely used as oxygen storage promoters, improving the catalyst’s ability to handle transient A/F ratio fluctuations 1. Ceria also promotes reducibility and stabilizes noble metal catalysts in a dispersed state, hindering sintering at high temperatures by forming oxidized Pt-O-Ce bonds 24.

- Calcium (Ca): Research suggests that the addition of calcium to a phosphorus-poisoned catalyst can have a regenerating effect, indicating its potential as a promoter for mitigating phosphorus deactivation 11.

4. Chemical Poisoning: Mechanisms of Active Site Deactivation

Chemical poisoning is a critical degradation pathway, leading to the irreversible or semi-reversible deactivation of the catalyst’s active sites. This section details the atomic-level mechanisms for key poisons.

4.1. Sulfur Poisoning

Sulfur compounds, primarily H2S and SO2, are potent catalyst poisons. The mechanism involves the strong adsorption and reaction of sulfur species with the active metal sites, effectively blocking them and preventing reactant molecules from accessing the catalytic surface 17.

- Adsorption and Reaction: H2S reacts directly with active metal sites, leading to deactivation 17. SO2, particularly in diesel exhaust, interacts with copper-chabazite (Cu-CHA) catalysts used for NOx reduction. Studies have shown that SO2 reacts with the [Cu2II(NH3)4O2]2+ complex, forming CuI species and a sulfated CuII complex that accumulates within the zeolite pores 18. X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) confirms the formation of sulfated components (SO42-) 18.

- Impact on Performance: Sulfur poisoning significantly diminishes the catalyst’s ammonia (NH3) storage capacity, impairs transient NOx reduction efficiency, and induces premature ammonia leakage 19. Higher SO2 concentrations accelerate this deactivation 19.

- Reversibility and Regeneration: Some sulfur poisoning can be reversed by removing H2S from the feed or by passing an inert gas through the catalyst bed, indicating an equilibrium between gaseous and adsorbed H2S 20. However, the binding energy of some sulfated species (SO42-) remains largely unaffected post-regeneration, especially those formed under high sulfur concentrations, making their removal difficult 18. Sulfur-ammonia species can be decomposed at 500°C, partially restoring NOx reduction performance, while sulfur-copper species require higher temperatures (600°C) for only partial restoration 19. High-temperature oxidation can be an effective regeneration method 17. The severity of SO2 poisoning underscores the necessity of ultra-low sulfur diesel fuel to mitigate catalyst deactivation in diesel exhaust systems 18.

- Competition with Coking: While coking (carbon deposition) is another deactivation mechanism, particularly in hydrocarbon reactions, the presence of cerium in the catalyst can enhance its resistance to carbon deposition, making sulfur poisoning a more significant deactivation factor in such cases 17.

4.2. Phosphorus Poisoning

Phosphorus, primarily from lubricating oil additives like ZDDP, deactivates catalysts by forming a physical barrier and chemically interacting with the washcoat.

- Glaze Formation: Phosphorus compounds, such as phosphates and zinc pyrophosphate, form a glassy layer or glaze over the catalyst surface 7. This glaze physically seals the passages within the washcoat, preventing exhaust gases from reaching the active sites 7.

- Interaction with Washcoat: Phosphorus compounds interact chemically with washcoat components like alumina (Al2O3) and ceria (CeO2), forming stable phosphates (e.g., cerium, zirconium, aluminum, and titanium phosphates) 7. This interaction primarily affects the oxide components of the catalyst, rather than directly poisoning the noble metals 11. The formation of these stable compounds can alter the washcoat’s pore structure and reduce its surface area, further hindering catalytic activity.

4.3. Lead Poisoning

Lead, historically from leaded gasoline, is a highly detrimental and largely irreversible catalyst poison.

- Surface Coating and Alloying: Lead compounds, upon combustion, deposit on the catalyst surface, forming a non-porous coating that physically blocks the active sites 10. Additionally, lead can alloy with the noble metals (Pt, Pd, Rh), fundamentally altering their electronic structure and rendering them catalytically inactive 10. This mechanism is particularly severe, leading to rapid and significant degradation of catalyst performance 7.

4.4. Silicon and Zinc Poisoning

- Silicon: Silicon compounds, often from coolant leaks or contaminated fuels, can deposit as silica (SiO2) on the catalyst surface or clog oxygen sensors 7. Silica deposition on the catalyst acts as a physical barrier, masking active sites and reducing the effective surface area. Clogging of oxygen sensors leads to inaccurate air/fuel ratio control, causing the engine to run sub-optimally and potentially exacerbating other degradation mechanisms 7.

- Zinc: Similar to phosphorus, zinc from oil additives forms oxides during combustion that contribute to the glaze formation on the catalyst surface, further reducing its efficiency by covering active sites 7.

In summary, chemical poisoning mechanisms involve the formation of strong chemical bonds or physical barriers on the catalyst’s active sites and washcoat, leading to a permanent reduction in catalytic activity and conversion efficiency. The reversibility of poisoning depends heavily on the specific poison, its chemical form, and the operating conditions.

5. Thermal Degradation (Sintering): Impact of High Temperatures on Catalyst Structure

Thermal degradation, particularly sintering, is a major cause of catalytic converter deactivation, especially at temperatures exceeding 500°C [L.5.3]. This process involves the irreversible loss of active surface area due to the agglomeration of noble metal particles and the structural collapse of the washcoat.

5.1. Noble Metal Sintering

Sintering refers to the growth of noble metal particles (Pt, Pd, Rh) at elevated temperatures, leading to a reduction in the total active surface area available for catalytic reactions 22.

- Mechanism: Noble metal particles, initially highly dispersed on the washcoat, can migrate across the support surface and coalesce (particle migration and coalescence) or larger particles can grow at the expense of smaller ones (Ostwald ripening) 24. This process is accelerated by high temperatures and the presence of water vapor 24.

- Platinum’s Susceptibility: Platinum (Pt) is particularly susceptible to sintering, especially in oxidizing atmospheres 22. Suppressing Pt sintering is crucial for catalyst durability 22.

- Support Material Influence: The choice of support material significantly affects sintering behavior. Ceria-based oxides (CeO2) are effective supports for Pt because they can form strong Pt–O–Ce bonds, which act as “anchors” to suppress Pt sintering 23. The strength of this interaction correlates with the electron density of oxygen in the support oxide 23. Conversely, zirconia-based oxides (ZrO2) are more suitable for Rh, especially in oxidizing conditions, due to Rh’s stronger interaction with oxide supports when Rh is in an oxide state 22. An optimized catalyst configuration often involves Pt loaded on ceria-based oxide and Rh on zirconia-based oxide to suppress sintering of both metals 22.

- Water’s Role: Water (H2O) can significantly influence sintering. At temperatures above 500°C, water’s inhibitory effect on catalytic activity becomes negligible, and Pd sintering becomes more prominent 24. In the absence of H2O, Ostwald ripening is favored, but in the presence of H2O, the formation of silanol (Si-OH) groups can favor the migration and coalescence of Pd on SiO2 supports 24.

5.2. Washcoat Structural Collapse

The washcoat itself can undergo thermal degradation, leading to a reduction in its high surface area and pore volume.

- Mechanism: Sustained high temperatures can cause the porous washcoat structure to collapse, reducing the available surface area for noble metal dispersion and catalytic reactions [L.5.3]. This is often associated with phase transformations or crystallite growth within the washcoat material.

- Impact: A reduction in washcoat surface area directly translates to a reduction in the number of available active sites, even if the noble metals themselves do not sinter as severely. This also affects the oxygen storage capacity of materials like ceria, further impairing catalyst performance.

The interplay between noble metal sintering and washcoat degradation is complex. Strong metal-support interactions, such as the Pt-O-Ce bonds, are vital for stabilizing the noble metals and preventing their agglomeration, thereby enhancing the catalyst’s thermal stability 24. Calcination pretreatment of support materials can also influence noble metal dispersion and resistance to sintering 26.

6. Physical Degradation: Erosion, Masking, and Mechanical Damage

Beyond chemical and thermal degradation, catalytic converters are also susceptible to physical damage from exhaust gas components and mechanical stresses.

6.1. Soot Masking

Soot, primarily from diesel combustion, can physically block the active sites of the catalyst, a phenomenon known as masking 27.

- Mechanism: Soot particles deposit on the catalyst surface, forming a physical barrier that hinders the diffusion of exhaust gases to the catalytic sites, thereby reducing conversion efficiency 27. On Diesel Particulate Filters (DPFs), soot deposition progresses through stages: deep bed deposition, particle tree growth, particle tree connection, and finally, the formation of a soot cake layer 28. This cake layer can reach a thickness of 20-50 microns 28.

- Impact on SCR Catalysts: Soot loading on SCR-coated filters increases ammonia (NH3) slip during adsorption and decreases NOx conversion 29. The effect of soot on catalytic activity is primarily physical, creating diffusion barriers, rather than chemical interactions 29. In filters with integrated SCR catalysts, the reaction of NO2 with soot can even compete with the desired fast SCR reaction 29.

- Soot Characteristics: The effectiveness of soot oxidation is influenced by soot composition and microstructure, which vary based on fuel, lubricating oil, engine type, and operating conditions 27. Real engine soot often has a “shell-like” structure with a crystallized graphite-like core, leading to higher ignition temperatures compared to amorphous carbon 34. Tight soot-to-catalyst contact improves reaction rates, but real-world DPF conditions often resemble loose contact 30.

6.2. Washcoat Erosion

The continuous flow of hot exhaust gases, especially those containing particulate matter, can lead to the physical erosion of the washcoat.

- Mechanism: Substrate erosion requires the presence of particulate matter in the exhaust stream 35. The extent of erosion depends on factors such as particulate velocity, size, morphology, and impingement angle 35. Non-uniform exhaust flow can also contribute to localized erosion of the substrate face, reducing the active surface area 27.

- Factors Influencing Erosion: Erosion is generally reduced at higher temperatures 35. The increasing use of high cell density and thin-wall substrates (e.g., 600/4, 600/3, 900/2) to meet stringent emission standards and reduce precious metal costs also raises concerns about their susceptibility to erosion 35.

- Mitigation: Technologies to reduce mat mount erosion, such as wire mesh seals, rigidizers, silica cloth edge treatment, and polycrystalline edge seals, are employed to protect the catalyst 33.

6.3. Mechanical Damage

Catalytic converters are subjected to significant mechanical stresses during vehicle operation, which can lead to structural damage.

- Vibrations: Engine and road vibrations can cause the ceramic monolith to crack or fracture, especially at mounting points or due to inadequate packaging.

- Thermal Shock: Rapid temperature changes, such as those experienced during cold starts or sudden engine shutdowns, can induce thermal stresses that lead to cracking of the ceramic substrate 47. The close-coupled placement of catalytic converters, designed for faster light-off, exacerbates concerns about structural damage due to severe thermal and mechanical conditions 35.

- Substrate Collapse: Severe mechanical or thermal stresses can lead to the complete collapse of the substrate, blocking exhaust flow and causing significant engine performance issues 53. High washcoat loadings, while increasing active surface area, can adversely affect the physical durability of advanced catalysts, particularly in close-coupled applications 61.

These physical degradation mechanisms directly reduce the effective catalytic surface area, impede mass transfer of pollutants, and can lead to catastrophic failure of the converter.

7. Influence of Operating Conditions on Degradation Rates

Engine operating conditions play a pivotal role in accelerating or mitigating the rates of chemical poisoning, thermal degradation, and physical damage.

7.1. Normal Stoichiometric Operation

For three-way catalytic converters, maintaining a precise stoichiometric air-to-fuel (A/F) ratio (λ=1) is crucial for optimal performance 4. Deviations from this narrow “catalyst window” can lead to incomplete conversion of pollutants and, in some cases, contribute to catalyst degradation. For instance, at lean mixtures, exhaust gases have high NOx and low CO/HC, while rich mixtures have high CO/HC and low NOx 5. Precise A/F ratio control, often achieved with feedback from an oxygen sensor, is essential 5.

7.2. Misfires

Engine misfires, where the air-fuel mixture in one or more cylinders fails to combust correctly, are highly detrimental to catalytic converters 52.

- Unburnt Fuel Overload: Misfires cause large amounts of unburnt fuel to enter the exhaust system and subsequently the catalytic converter 52. Catalytic converters are not designed to handle such high concentrations of raw fuel 53.

- Overheating: The unburnt fuel ignites within the catalytic converter due to the high internal temperatures (normal operating range: 1200-1600°F) 53. This combustion within the converter causes extreme overheating, potentially exceeding 2000°F, turning the converter bright red 56.

- Structural Damage: This extreme heat can melt or damage the internal structure of the converter, leading to clogging or complete failure 53. The melted material restricts exhaust flow, further degrading engine performance and fuel efficiency 53.

- Consequences: Misfires can cause premature catalytic converter failure, leading to reduced vehicle power, poor fuel economy, and increased emissions 53. Symptoms include lower fuel efficiency, check engine light illumination (P0420 or P0430 codes), poor acceleration, power loss, engine hesitation, stalling, a sulfur smell, and excessive heat buildup 55.

- Causes of Misfires: Misfires can result from a lean burn condition (too much air), leaking fuel injectors, or even a failing oxygen sensor causing a rich air-fuel mixture 56. Modern engine management systems are designed to detect misfires early and alert drivers 52. Prompt maintenance is essential to prevent severe damage 53.

7.3. Prolonged Rich/Lean Excursions

While brief excursions are managed by the oxygen storage capacity, prolonged operation outside the stoichiometric window can accelerate degradation.

- Rich Conditions: Excess fuel can lead to carbon deposition (coking) on the catalyst surface, masking active sites and reducing efficiency [L.5.5]. It can also lead to the formation of metal carbonyls (e.g., Ni(CO)4) at lower temperatures and high CO partial pressures, causing catalyst loss [L.5.10].

- Lean Conditions: Excess oxygen can promote the oxidation of sulfur compounds to more stable sulfates, which are harder to remove and contribute to irreversible poisoning 18. It can also accelerate noble metal sintering, particularly for platinum 22.

7.4. Cold Starts and Transient Events

- Cold Starts: During cold starts, the catalyst is below its light-off temperature, meaning it is ineffective at converting pollutants [L.5.1]. This period contributes significantly to overall emissions. The catalyst’s warm-up time is crucial for light-off 38.

- Transient Events: Rapid changes in engine load and speed lead to fluctuations in exhaust gas composition and temperature. While oxygen storage components help, prolonged or severe transients can stress the catalyst, accelerating thermal degradation and potentially leading to mechanical fatigue.

7.5. Temperature Management

The operating temperature of the catalyst is critical. While high temperatures accelerate sintering, a certain temperature is necessary for the catalytic reactions to occur efficiently. For instance, in biomass pyrolysis vapor upgrading, increasing catalyst temperature can counteract deactivation, but the rate of increase needs optimization [L.5.8]. An optimal operating temperature range exists for catalysts, balancing conversion efficiency and minimizing coke formation [L.5.11].

8. Consequences of Degradation: Performance Metrics and Emissions Impact

Catalyst degradation manifests in quantifiable performance metrics, directly impacting vehicle emissions compliance and overall functionality.

8.1. Reduced Conversion Efficiency

The most direct consequence of catalyst degradation is a decrease in its ability to convert harmful pollutants into benign substances.

- Active Site Loss: Chemical poisoning, thermal sintering, and physical masking all lead to a reduction in the number of available active sites on the catalyst surface [L.5.4][L.5.5][L.5.6]. This directly translates to fewer reaction pathways for pollutants.

- Pollutant-Specific Impact:

- Hydrocarbons (HC) and Carbon Monoxide (CO): Reduced active surface area means less efficient oxidation of these compounds.

- Nitrogen Oxides (NOx): Deactivation of rhodium sites or poisoning by sulfur can severely impair NOx reduction capabilities 19.

- Factors Affecting Conversion: Conversion efficiencies are influenced by vehicle operating conditions, including gas species concentrations, temperature, and mass flow rate at the catalyst inlet 39. Washcoat formulation also plays a role, impacting light-off performance and pressure drop 46. At low space velocities, ceramic substrates may show better conversions, while metallic substrates might perform better at high space velocities due to larger geometric surface area 39.

8.2. Elevated Light-Off Temperature (T50, T90)

The light-off temperature (T50 or T90, representing the temperature at which 50% or 90% of a pollutant is converted, respectively) is a critical indicator of catalyst performance.

- Increase in Light-Off Temperature: Catalyst deactivation, whether due to poisoning, coking, or thermal degradation, invariably leads to an increase in the light-off temperature required for efficient pollutant conversion [L.5.1]. This means the catalyst takes longer to become effective after a cold start, leading to higher emissions during the warm-up phase.

- Mechanism: The increase in light-off temperature is a direct result of the reduced active surface area and the diminished intrinsic activity of the catalyst. For instance, strong CO adsorption on catalytic sites can impede O2 adsorption at low CO conversions, resulting in U-shaped light-off curves [L.5.9]. Once CO desorbs, the reaction proceeds rapidly [L.5.9].

- Engine Operating Conditions: Light-off temperature varies with engine speed and torque due to changes in exhaust flow rate [L.5.2]. Light-off curves are highly dependent on reaction conditions, making extrapolation to other conditions (flow rates, catalyst amount, reactant concentrations) challenging [L.5.11].

8.3. Emissions Impact and Compliance

The consequences of degradation directly impact a vehicle’s ability to meet stringent emission regulations.

- Increased Tailpipe Emissions: Reduced conversion efficiency and elevated light-off temperatures mean that more unburnt hydrocarbons, carbon monoxide, and nitrogen oxides are released into the atmosphere, contributing to air pollution.

- Failure of Emission Tests: Vehicles with degraded catalytic converters will likely fail mandatory emission tests, leading to costly repairs and potential legal implications.

- Diagnostic Trouble Codes: Catalyst inefficiency often triggers diagnostic trouble codes (DTCs) such as P0420 or P0430, indicating that the catalyst’s performance is below a specified threshold 53.

In essence, catalyst degradation compromises the very purpose of the catalytic converter, leading to environmental harm and operational issues for the vehicle.

9. Mitigation Strategies and Future Catalyst Technologies

Addressing catalytic converter degradation is a continuous challenge in automotive engineering. Current and emerging strategies focus on enhancing durability, improving catalyst formulations, and optimizing engine management.

9.1. Fuel and Lubricant Quality

- Ultra-Low Sulfur Fuels: The most effective way to prevent sulfur poisoning is to use fuels with ultra-low sulfur content 18. This significantly reduces the amount of sulfur compounds entering the exhaust system.

- Low-Phosphorus/Zinc Oils: Reducing or replacing zinc dithiophosphate (ZDDP) in lubricating oils minimizes phosphorus and zinc contamination 7. Zinc replacement additives can provide necessary lubrication without the detrimental effects of ZDDP 15.

9.2. Engine Management and Maintenance

- Prompt Misfire Correction: Modern engine management systems are designed to detect misfires early 52. Addressing engine misfires, leaking fuel injectors, and coolant leaks promptly prevents excessive unburnt fuel, oil, and coolant from entering the catalytic converter, thereby preventing severe overheating and damage 7.

- Precise Air-Fuel Ratio Control: Maintaining the engine’s air-fuel ratio within the optimal stoichiometric window for TWCs is crucial for maximizing conversion efficiency and minimizing conditions that accelerate degradation 5.

- Adsorbents: Using solid adsorbents (e.g., alumina, activated charcoal, cordierite, zeolite) to remove phosphorus compounds from crankcase ventilation and exhaust gas recirculation streams can protect the catalyst from poisoning 7.

9.3. Advanced Catalyst Formulations and Washcoat Materials

Significant research and development are focused on creating more robust and efficient catalysts.

- Improved Washcoat Materials:

- High Surface Area and Thermal Stability: Washcoat materials like gamma-alumina (γ-Al2O3), zeolites, silica (SiO2), titania (TiO2), ceria (CeO2), zirconia (ZrO2), vanadia (V2O5), and lanthanum oxide (La2O3) are continuously being refined for higher specific surface area (BET typically 100-200 m22/g) and enhanced thermal stability 57.

- Additives: Additives like Evonik’s AEROSIL fumed silica, AERODISP silica dispersions, and AEROPERL (fumed silica, titania, alumina oxides with spherical particles) are used to fix precious metals and enhance the stability of the catalytic layer 58.

- Multi-Layer Washcoats: Employing multi-layer washcoats allows for different chemical formulations in each layer, optimizing performance and durability 57.

- Novel Catalyst Formulations:

- Optimized Noble Metal Dispersion: Strategies focus on creating strong metal-support interactions (e.g., Pt-O-Ce bonds) to anchor noble metal particles and suppress sintering, leading to higher catalytic activity and durability 23. An optimized configuration involves Pt on ceria-based oxide and Rh on zirconia-based oxide 22.

- Trimetallic and Bimetallic Catalysts: Advanced metallic catalyst formulations, such as trimetallic K6 (Pt:Pd:Rh) and bimetallic K7 (Pd+Pd:Rh), are designed to combine the NOx reduction properties of Pt:Rh with the HC oxidation activity of Pd, often incorporating special catalyst structures with optimized washcoat performance for improved light-off, thermal stability, and transient performance 59.

- Perovskites and Mixed Oxides: Research into complex mixed oxides and perovskite structures offers potential for developing catalysts with high activity and improved resistance to poisoning and sintering, potentially reducing reliance on expensive noble metals.

9.4. Novel Substrate Designs

- Metallic Substrates: Metallic substrates are being explored for their ability to design catalysts that are more effective under low exhaust temperature conditions and have improved oxygen storage properties in the washcoats 59. They also offer advantages in terms of tooling flexibility and integrated skins for welding 37.

- High Cell Density and Thin Walls: Catalyst supports with higher cell density, smaller wall thickness, higher surface area, and lower thermal mass are desirable for faster light-off and higher conversion efficiency 61. However, high washcoat loadings on these designs can affect physical durability 61.

- Close-Coupled Applications: For close-coupled converters, optimization of substrate/washcoat interaction, geometric design, and mounting systems are crucial for light-off performance and FTP efficiency 61.

9.5. DPF Regeneration Strategies

For diesel systems, effective DPF regeneration is key to preventing soot masking.

- Passive Regeneration: Utilizes catalysts to lower the soot oxidation temperature, allowing continuous regeneration during normal operation 42. NO2-assisted regeneration, where NO is oxidized to NO2, is particularly effective as NO2 is a stronger oxidant for carbon than oxygen 43.

- Active Regeneration: Involves increasing exhaust temperatures (e.g., via fuel injection) to burn off accumulated soot 42. Forced regeneration may be necessary if the DPF becomes too clogged 42.

- Impact on SCR: Increased temperatures during DPF regeneration can negatively impact NOx conversion efficiency in engines with SCR aftertreatment 43.

9.6. Future Directions and Speculation

- Self-Healing Catalysts (Speculation): While currently in early research phases, the concept of self-healing catalyst materials that can repair active sites or washcoat structures damaged by poisoning or sintering holds immense potential for extending catalyst lifespan. This could involve materials that release active components or undergo structural rearrangements to restore functionality under specific conditions.

- Advanced Sensor Integration and AI/ML for Predictive Maintenance (Speculation): Integrating more sophisticated in-situ sensors that can monitor catalyst degradation in real-time (e.g., active surface area, specific poisoning levels) could enable highly precise, predictive maintenance. Machine learning algorithms could analyze these sensor data streams, combined with engine operating parameters, to predict catalyst failure before it impacts emissions, allowing for proactive intervention rather than reactive replacement. This could also optimize regeneration cycles for DPFs and SCRs.

- Biofuel Compatibility: As biofuels become more prevalent, understanding and mitigating the impact of new contaminants (e.g., silicon from improperly recycled ethanol) on catalyst poisoning will be crucial 7.

- Sustainable Catalyst Materials: The drive for sustainability will continue to push for reduced reliance on precious metals and the development of more abundant, cost-effective, and environmentally friendly catalyst materials 60.

The average catalyst life has already increased significantly from 2-3 years to 5-6 years due to advancements in catalyst preparation [L.5.12], highlighting the continuous progress in this field.

10. Conclusion

The effectiveness and longevity of catalytic converters are profoundly influenced by the complex interplay between exhaust gas composition, engine operating conditions, and the inherent material science of the catalyst. Chemical poisoning, thermal degradation (sintering), and physical damage (masking, erosion, mechanical stress) represent the primary pathways through which exhaust gas components compromise catalyst performance. Each mechanism leads to a reduction in active surface area and an increase in the light-off temperature, directly impacting the ability to meet stringent emission standards.

Understanding the atomic-level interactions of poisons like sulfur, phosphorus, lead, zinc, and silicon with noble metals and washcoat materials is critical for developing more resilient catalysts. Similarly, mitigating noble metal sintering through optimized support materials and strong metal-support interactions is paramount for thermal durability. Physical degradation, driven by particulate matter and mechanical stresses, necessitates robust substrate designs and effective regeneration strategies.

Ongoing advancements in washcoat materials, catalyst formulations, and intelligent engine management systems are continuously pushing the boundaries of catalyst durability and efficiency. The future of emissions control will likely involve a synergistic approach, combining advanced materials science with sophisticated engine and aftertreatment control strategies, potentially incorporating self-healing capabilities and AI-driven predictive maintenance, to ensure cleaner air and sustainable mobility.